Brooks Brothers at Fifteen

The bedroom smelled of the cedar that lined his father’s open closet. His mother always left his father’s closet open, allowing her a view of the neat row of hanging suits across from her bed. Looking at those suits, he imagined them as cocoons within which numerous fathers were all undergoing their various private metamorphoses. Not gone forever, these imagined fathers were merely in a state of becoming. Just as he and his mother were changing away from the creatures that they had once been.

He touched her elbow--a soft point that cradled her head. Limbs curled in on themselves as the lines of a Greek key inevitably spiral toward a center point. “Can I get you anything?” he asked her. Dull and puffy, her eyes remained fixed on the dead forest within which his father’s clothes hung. A small abstraction of a moan, or a remote sob—the distinction had become blurred over time—parted her pale lips. “Mom?” he gently asked. In response came the continuing daily quiet. He closed her door softly, walked down the dark hallway, and emerged into his private world; a large house empty of childhood.

Grabbing a couple of cassette tapes from his room, he retrieved a bong hidden in the bushes outside by the back of the house, and walked toward the quarter acre that constituted the “far back”. His father was waiting for him, sitting under the large old avocado trees.

Beneath those trees, in the dirt, a circle of chairs surrounded two old milk crates covered with a batiked cloth. Dad hadn’t aged. He was still forty-eight years old with hair silvering, shining, and long in comparison with the conservatism of his clothes: a dark grey Brooks Brothers suit, light blue dress shirt, and a dark blue paisley tie. The same age as that last day he had seen him three years ago. He was starting to get used to the fact that his father would come and sit with him under the tree. Dad rarely spoke. He just seemed to watch.

Sitting down, he took a lid of weed from his shirt pocket. “How can she cry so much? I mean, her eyes are always so red, so raw. You know I don’t cry as much as I used to. I don’t have time I guess. You know? What should I do for her? I mean, you know? I mean…” his voice trailed off as he stared at his father who was leaning back in a chair.

Trying again, he said, “Let me ask you something…why did all this have to happen? I mean, where’s God anyway? You know you made me kind of believe in that stuff. God and stuff. Then, well, I guess you made me not believe in God. I don’t know. But you’re here and you shouldn’t be, and I think you’re real. But I know you can’t be. And isn’t that like God? I mean, that he’s real even though he can’t be? Not that you’re God. I know that, I guess.”

Removing the bowl from the stem of the bong, he blew through the hole, and filled it with some of the pot from the baggie. The late afternoon summer sun, leaking through the avocado trees, cast long dappling shadows in the heat. Pulling a tape deck from inside of one covered milk crate, he slipped a tape in. Pushing the play button, the silence from his father was drowned out. It was replaced with The Stones singing “Gimme Shelter.” He lit a match, stared at his dad for a second, and then pulled a bong load. While holding in the hit he saw his dad look away from him. This made him feel slightly ashamed.

“yeah we’re goin’ ta fade away…”Blowing out the smoke, he continued, “See, well…you know, um, mom hears things and I see things. I mean, I’ve heard you as well, but seeing grandpa the other day too? Wow that was creepy. You know? I mean, why would he come here? He was always disappointed in me after you were gone. I mean, I got kicked out of the Boy Scouts for refusing to pray! You know! So why did he come here? He just sat out by the swimming pool and stared into space. Did you know that he came here?”

Mick and Keith kept right on playing.

“Whoa…children…it’s just a shot away…it’s just a shot away, yea, yea, yea” He ignored the fact that his father never liked The Rolling Stones--or rock for that matter. Head bowed, his father stared at his own hands as if he had never seen them before, while a lock of silver hair slowly fell from his part across his forehead and right eye. Seeing that his father was no longer paying attention, he set the bong down and picked up a dry avocado leaf. Crushing it, he smelled a spicy almost licorice scent.

“Okay so…you won’t tell me about why this is all happening to me. You know, I used to cry all the time, just like her, like mom. Now I need to show her that there’s another place…I mean, like, a totally different place. Where she doesn’t need to hurt so much. Why don’t you go and talk to her? I mean, she hears voices anyway…so what difference would it make if it was yours? That would be so much better than whatever it is she hears now, like, you know what I mean? Dad? I can’t make her see her way out of wherever she is now. She’s trapped wherever she is...I can tell you that.”

He stretched in his chair and looked at the sky up in between the canopy of leaves. When he looked back, his father was staring intently at him. Dad’s hand dropped a crushed avocado leaf onto the fine dirt. The smell made him sad.

“Are you real? Are you God? Or am I like her? You know, sick or whatever. I can’t have friends over anymore dad. If they saw mom they wouldn’t understand that she’s just really sad about you dying, you know? So it’s just you and me…and I guess grandpa now. Man, that was weird. Why did he come here? Can’t you tell me at least that?”

“You’ve got the silver…you’ve got the gold…” The sun hit him directly in the eyes washing out the world. “Yeah, I’ve got the silver. Hear that dad? Please tell me what I should do for her? Give me at least that, will you? Just say, ‘Well, blah blah blah.’ Okay? But you know, like you were still here and could actually tell me. Come on, please talk to me.”

Shifting in the chair, his father pushed his shining hair back into place. Blue eyes seemed to look right through him. Then his father reached out and placed another dried leaf on his lap.

“Crush that for me,” his father said. “I can’t smell it anymore. But I can smell it when you smell it. Do that for me.” His father stared at him, and waited. He didn’t like to see that sad confused yearning look in his father’s eyes. It reminded him of his mom.

“Wait…when I smell something you smell it too? So do you get stoned when I get stoned? That would be totally weird, I mean, getting stoned with my dad. No, that’s too weird.” He picked up the leaf from his lap and twirled it over and over.

Raising his face back to his father, he said, “Okay…no problem. But we’ll have to make a trade. I’ll crush up the leaf if you’ll tell me what to do for mom. Okay? I mean, that’s fair isn’t it? Like, you know, I would smell the leaf for you anyway. Even if you said no about telling me what to do for mom. Cause, it’s not like you’re real or anything. Unless you are. Oh God.” He started quietly laughing, “God…get it? Man.”

While talking he had pulled the avocado leaf into a position that covered his entire hand. This obscurity felt good to him. Each dried vein in the leaf was perfect. The red brown color was like old blood from a skinned knee. While he thought of the blood he saw doorways marked with lamb’s blood to ensure that the angel of death would pass by those huddled families within. The leaf had a slight curl that made him think of the ram’s horn made into a clarion to call those unaware to safety…or to arms. He thought of the bitters of the Exodus that he had eaten, and the questions of the youngest. He thought of Robert Johnson’s crossroads and he thought of his mother.

“…when all your love’s in vain…”Still looking at the perfection of the avocado leaf, he said, “Couldn’t you just let her see you? I mean, maybe then she would stop hearing all those things, and stop crying all the time, and…”

Then he started to shake. And the tears came. They came so violently that he couldn’t see anything. He couldn’t hear anything either, except for his own whimpering and sobbing. His nose began to run. Embracing himself, he doubled over placing his head in his own lap. Periodic convulsions wracked his body. Then he heard the leaf crush in his balled up fist. The perfect leaf veins poked at his palm, and the pungent anise odor of avocado spiced the air once again. On the back of his neck he felt a hand gently caress him.

“It’ll be okay. Your mom does see me. Just not the way you do. You’ll be okay. Cry now, it’s okay,” he heard Dad whisper to him.

Later he thought,

but it wasn’t okay was it? Those tears carried a corrosive acid that interfered with the rituals of his days. They seeped into his ability to search for the path out of the forest. They crusted his eyes over and blinded him. Someone had to have the vision to lead his mother out of bondage.

No more tears, he thought. No, never, ever, again.

Soon after that day of Shofars and lamb’s blood, of dead forests and pleading looks, he saw all his dead relatives hanging around the yard. All of them seemingly intent on some sort of meditation upon whatever were before them. Grandma stared at the stable. Grandpa continued his fascination with the pool. Two of his dead cousins showed up and just sat under the basketball hoop on the court where he had played that last game with his father—the last game before the metamorphosis. None of them said anything.

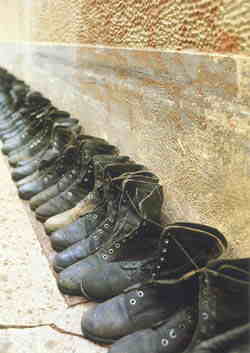

Within the maze that his mother lived in there was no trail of breadcrumbs to lead her back to him. She receded ever further into her solitary reality. Those tears that fell from her eyes never dried. The vision that she needed was beyond his ministrations. So, one day, he went into the house and began to place dried avocado leaves into the pockets of all of his father’s beautiful suits. They were placed into the shoes, shirts, and on top of the tie rack. He didn’t crush any. He didn’t want to stop his mother from smelling the dead cedar that lined the haunted forest of a closet. But he did want that forest to have some of the perfection that he had tasted in the bitters of Passover; the perfection of the leaf veins he shared with his father.

In his room he had strewn the floor with avocado leaves. Carefully hidden, under a pile of these leaves that he made by his bed, was a blue paisley tie of his dad’s. He decided to gather up as much glue as he could find in the house. He searched every room except for his parent’s bedroom. In all he found four large bottles of white glue. These were leftover from those ancient days of school projects or odd creations made on weekends.

The thought came to him of strands that caterpillars string out of themselves while creating a cocoon. It seemed that those strands were smears of the blood that lay inanimate within the dried avocado leaves; that lay inanimate within his father and relatives. This was the blood of the lamb. This was the blood of his inheritance. Then he took a long hot shower. Afterwards, he went back to the avocado trees, sat down, and waited.

When his father appeared he smoked some pot and crushed a bunch of leaves. The air carried no rival scents. He remained quiet, listening to the breeze rattle the wide green leaves which surrounded him like a vegetable umbrella. This was a personal Seder, an account to himself of how he too would return out of bondage to the Holy land. Still the youngest, he now understood those bitters that were his birthright. They were the smell and taste of the inside of his cocoon here under these trees.

After taking off all of his clothes, he had folded them neatly and placed them inside of one of the milk crates. The air was hot and his mouth was dry. He imagined that his veins looked perfect. Hanging from the tree was a thick climbing rope. Taking hold of this rope, he pulled himself up into the tree. A brown paper grocery bag came with him, held in his teeth, up onto the thick branch above. The bag was full of the crushed avocado leaves, the bottles of glue, and the tape deck. Through the boughs he could just see the top of the roof of the stable, it’s Spanish tiles red brown. Working in small areas at a time, he smeared glue over his skin. This process began with the upper left quarter of his body. After the glue was in place he pressed the crushed leaves onto his body, continuing until he was covered in glued on crushed leaves. He could smell the mix of avocado spice and white glue.

“How’s that smell dad?” he whispered to his father, who now sat on a branch across from him. “I kept my part of the bargain you know. I never quit. I never died. But you couldn’t tell me what to do for her could you? I gave you all these leaves…that’s what you asked for...wasn’t it? Then all these people, relatives, show up and they’re just zombies. So now I’ve got a gift for you.”

Pulling up the climbing rope from below, he fashioned a noose about midway down its length. The dried glue made his skin feel constricted. No, he felt held, like in some giant hand. It felt like the imaginary hand of his dad. Or God. He smiled. He put a tape into the tape deck that he had wedged into an elbow of the branch. Pushing play he heard,

“I’m your toy…I’m your old boy, and I don’t want no one but you to love me…” Slipping the noose over his head, he knocked some of the leaves off of his cheek. He watched as they twisted their way to the ground below. Then he tightened the noose around his neck and crouched on the thick knobby barked branch. To invite metamorphosis he would become a cocoon, a leaf suspended. To be passed over he would join himself with the perfect inanimate blood of the lamb-- the blood of his father and the blood of the leaves. Quietly he asked, “Why is this day different from all other days?” Then he bit into a fresh avocado leaf and tasted the bitter tang of belonging. Suddenly all his dead relatives crowded around under the tree. They left an opening directly below him. An invitation, he thought. Gram Parsons continued singing in the background,

“ No I wouldn’t lie…you know I’m not that kind of guy.”The late afternoon sun hit him in the eye and he heard something far away. At first it sounded like a horn.

The call to safety, he thought. As he slipped off the branch he heard his mother calling for him.

It was a mistake, he thought. But he knew he would at least be able to get her to see him. Like dad said she saw him. And he would ask her to crush up avocado leaves for him. And she would feel better then. The sun disappeared. He saw all his relatives gather leaves up and crush them. Then he called out to his mother, “I’ll be right there mom!”

after dennis cooper's poem

after dennis cooper's poem